Montreal Ballpark

It's 2019 and there's talk that our Major League Baseball team, the Expos, will return to Montreal. But they can’t play at the Olympic Stadium—it's a billion-dollar white elephant that amounts to a claustrophobic and decaying baseball venue. So what would a new ballpark for Montreal look like?

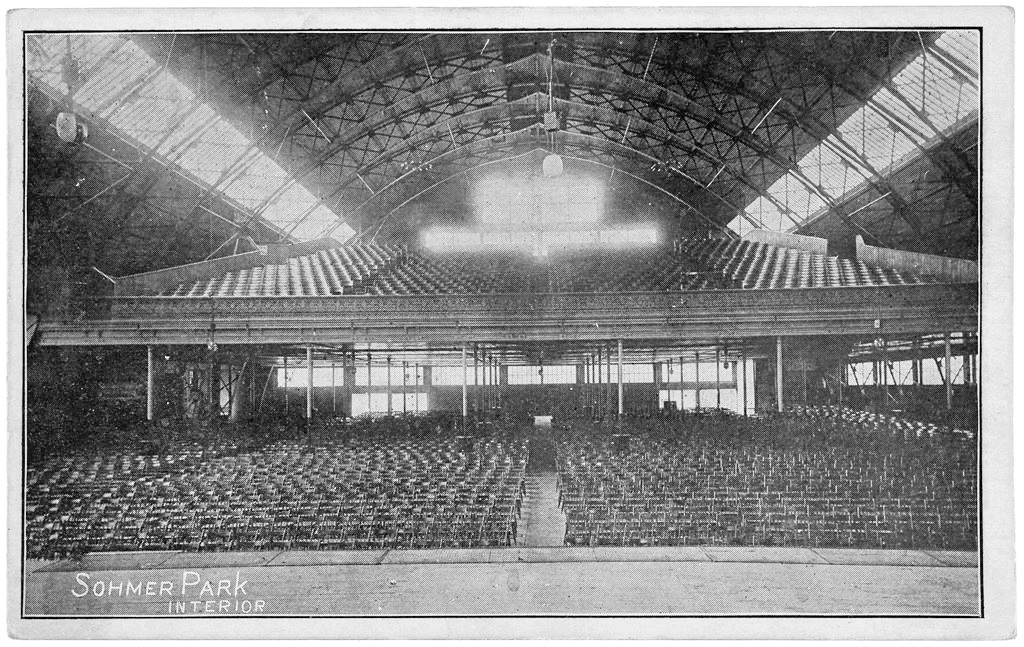

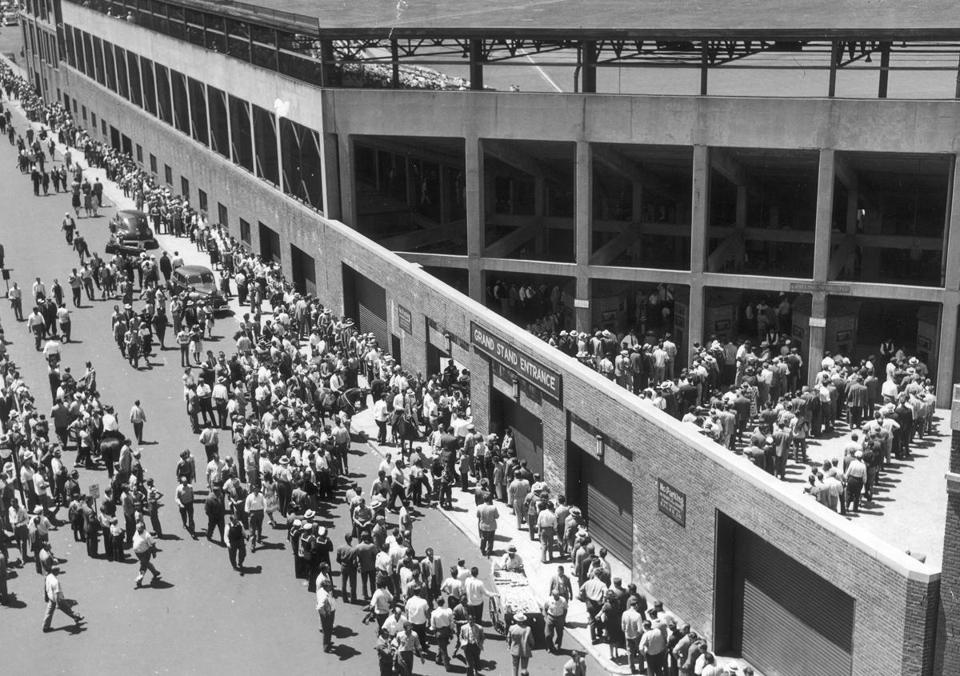

The American trend of the last thirty years is promising. Ballparks are more open, more nostalgic, more baseball-y, and overall more interesting urban venues. But looking back even further, it's important to understand that baseball and its venues were once tightly woven into the fabric and cultural identities of their cities (19th century industrial cities, specifically), while today’s stadia look more like private, exclusive resorts than the beloved civic venues they were a century ago.

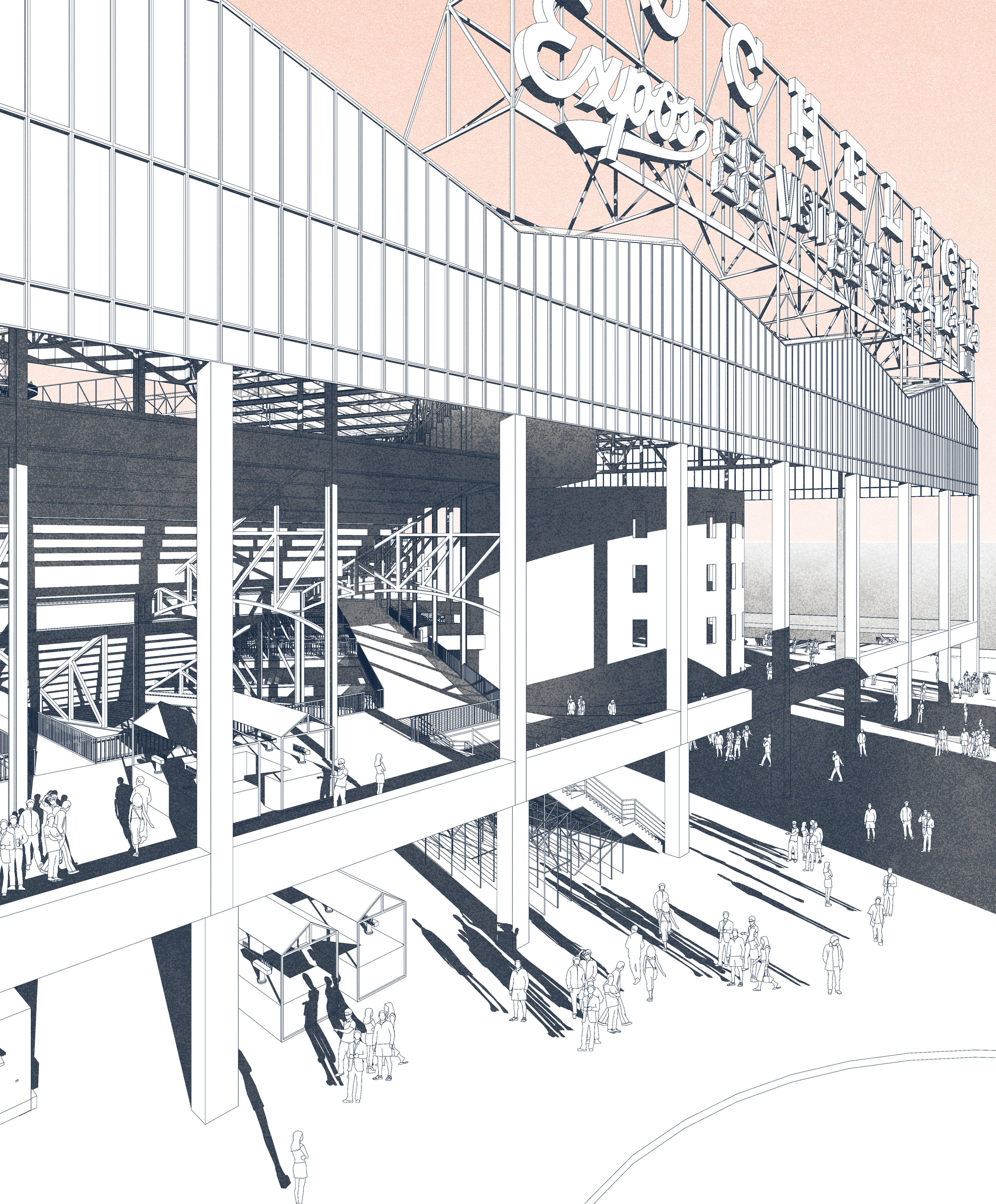

Sure, ballparks are richly programmed and full of public life on game days, but their many amenities—the concourse, bars, restaurants, suites—are tucked away within the building's belly and completely inaccessible for the remaining days in the season. How can baseball belong to the city again? How can it belong to Montreal?

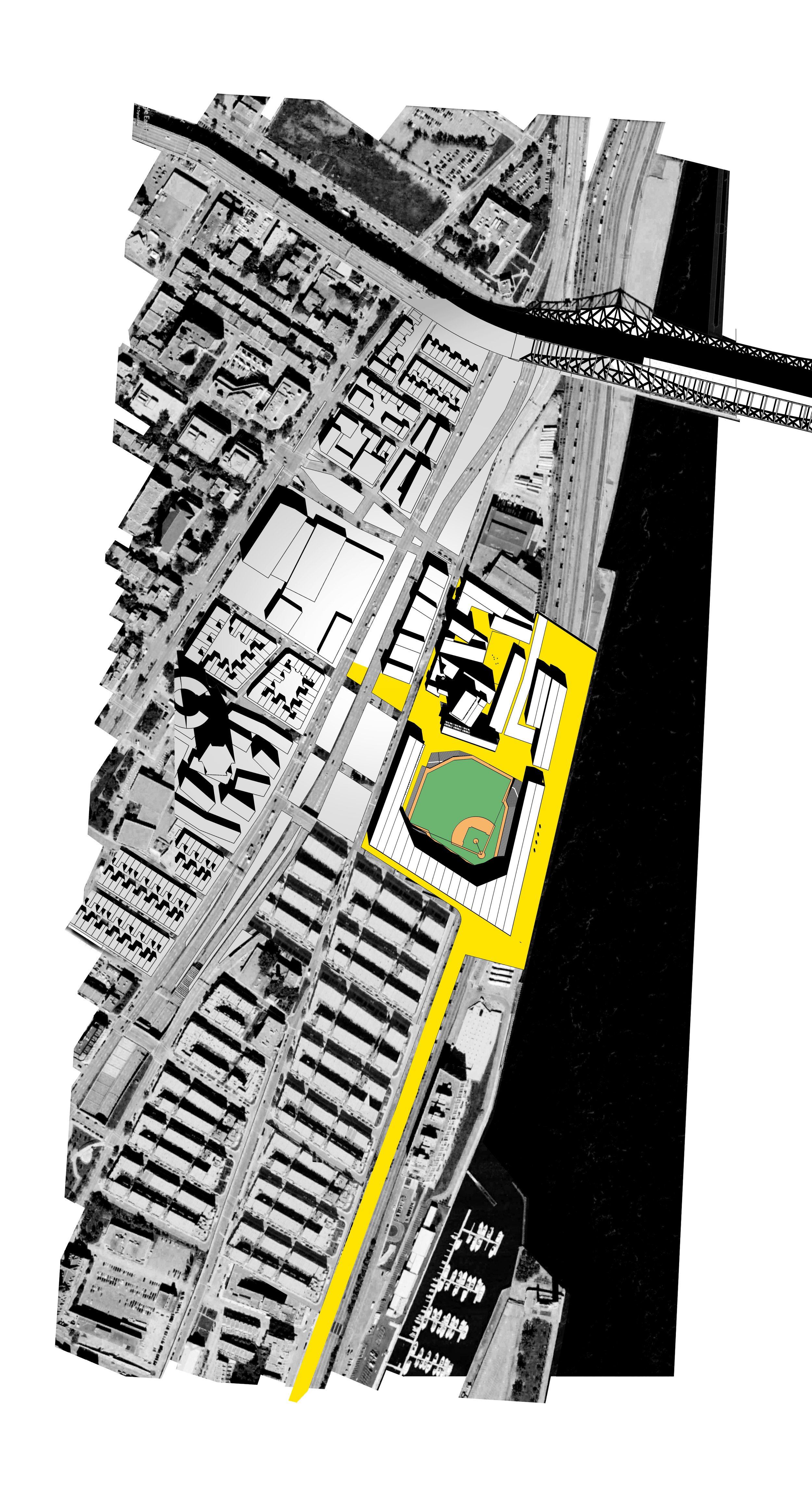

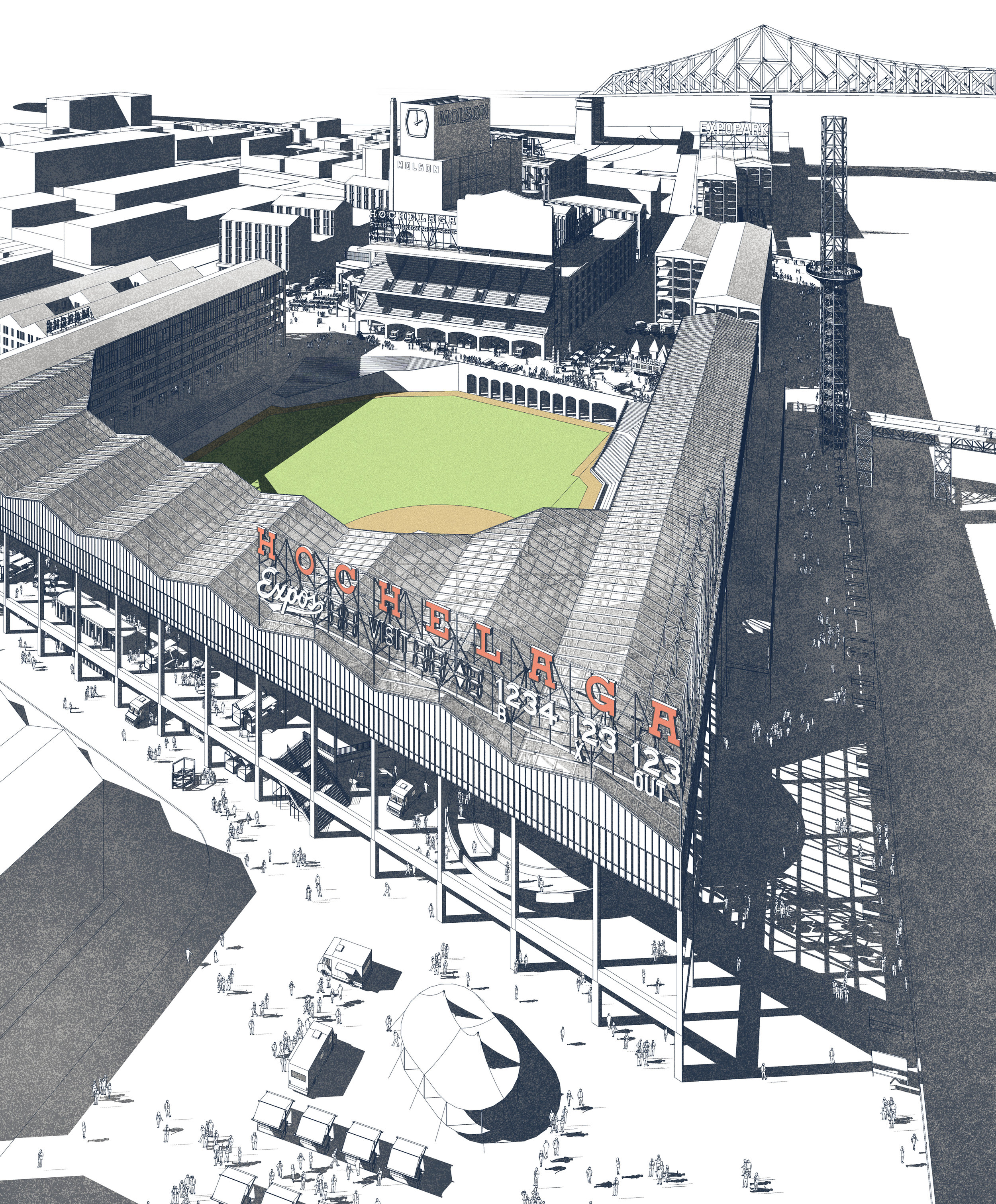

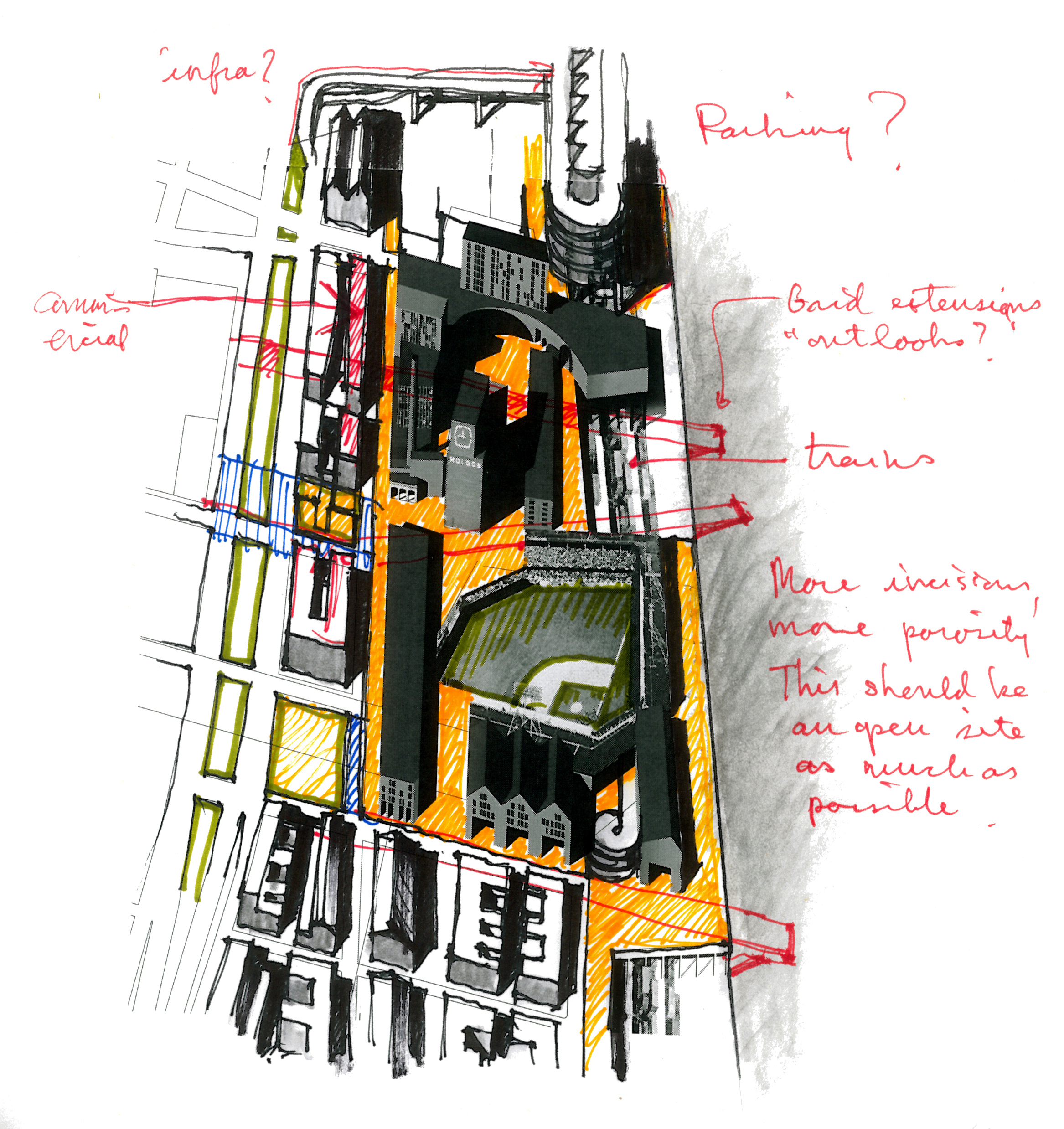

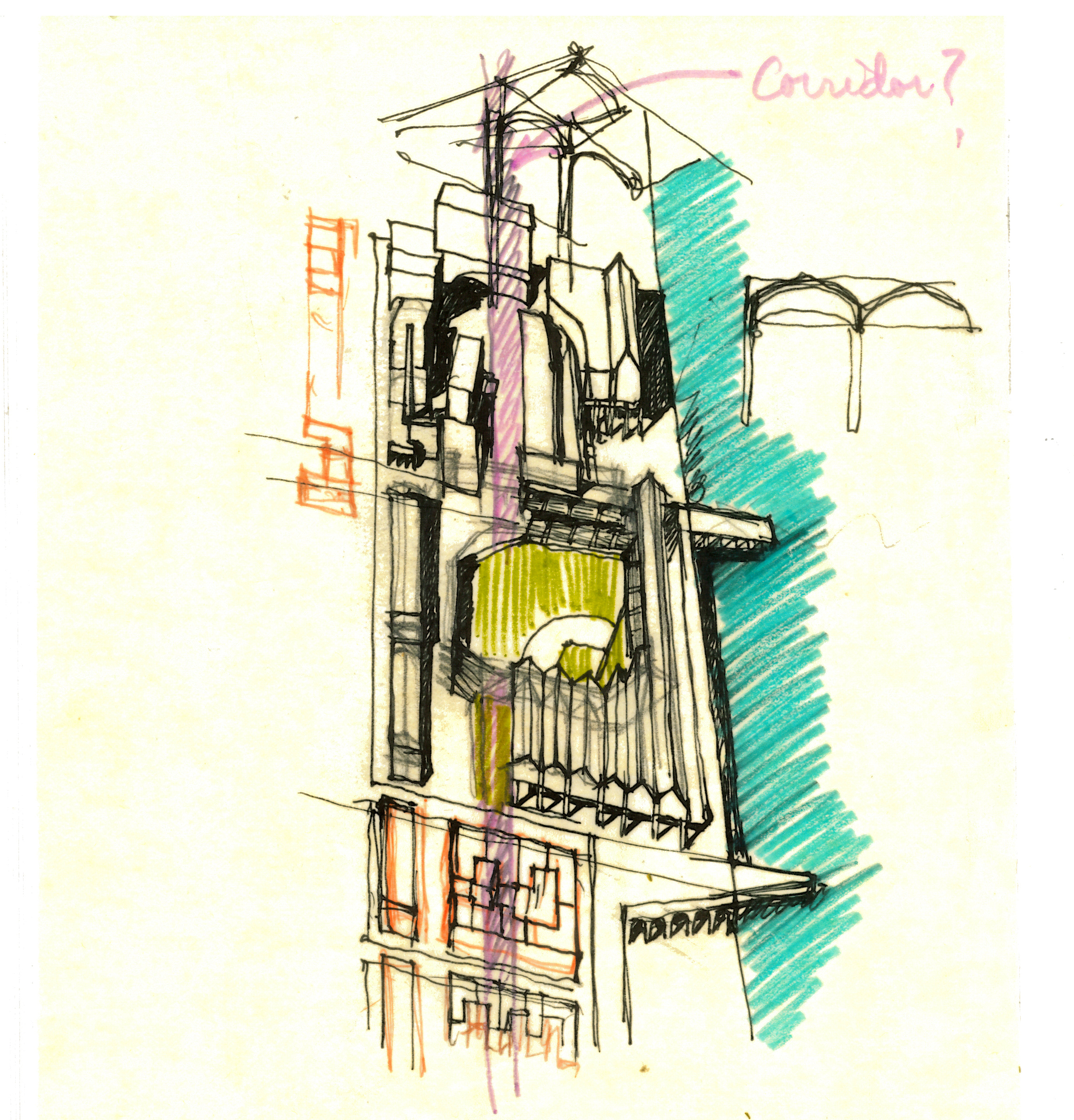

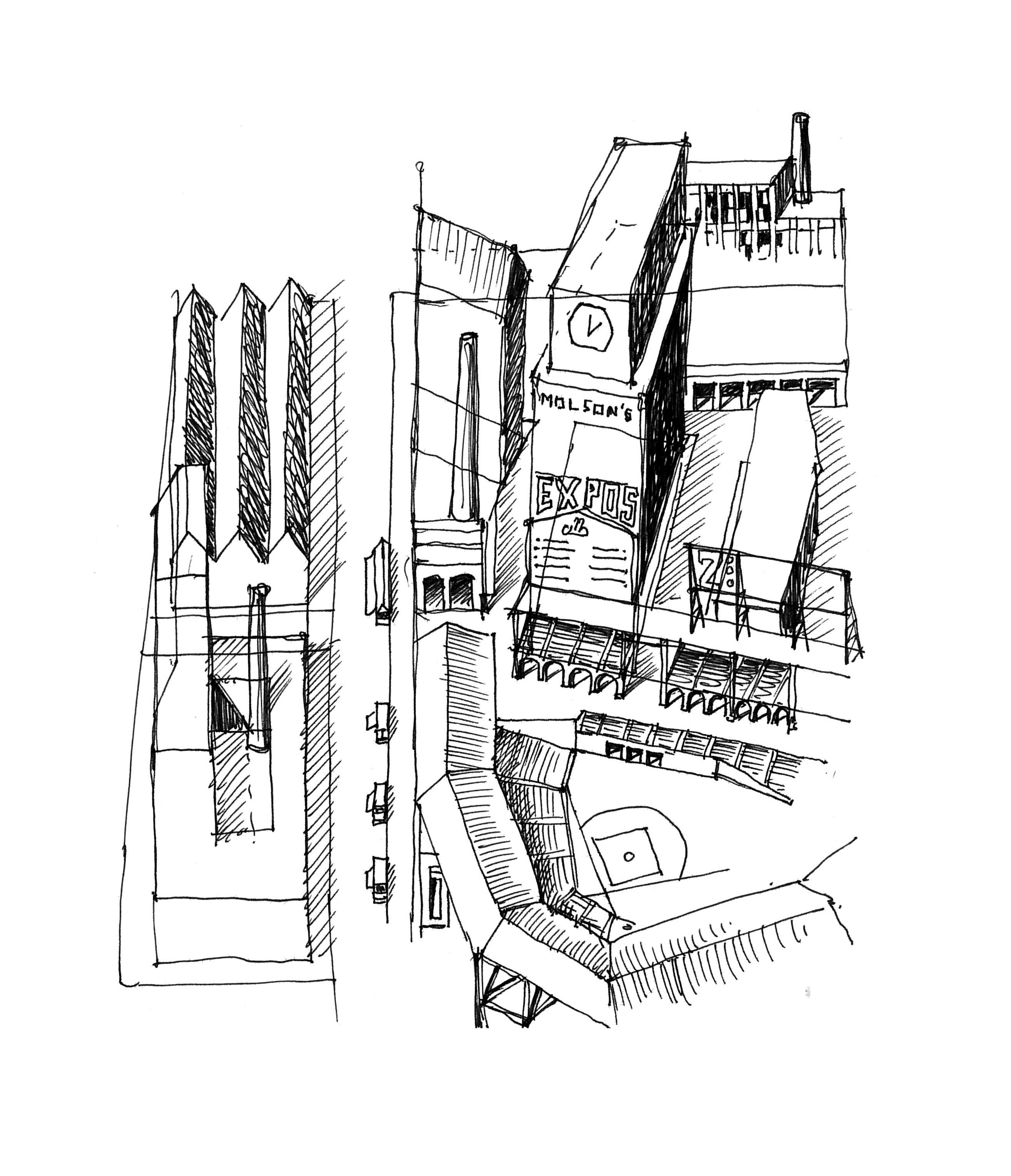

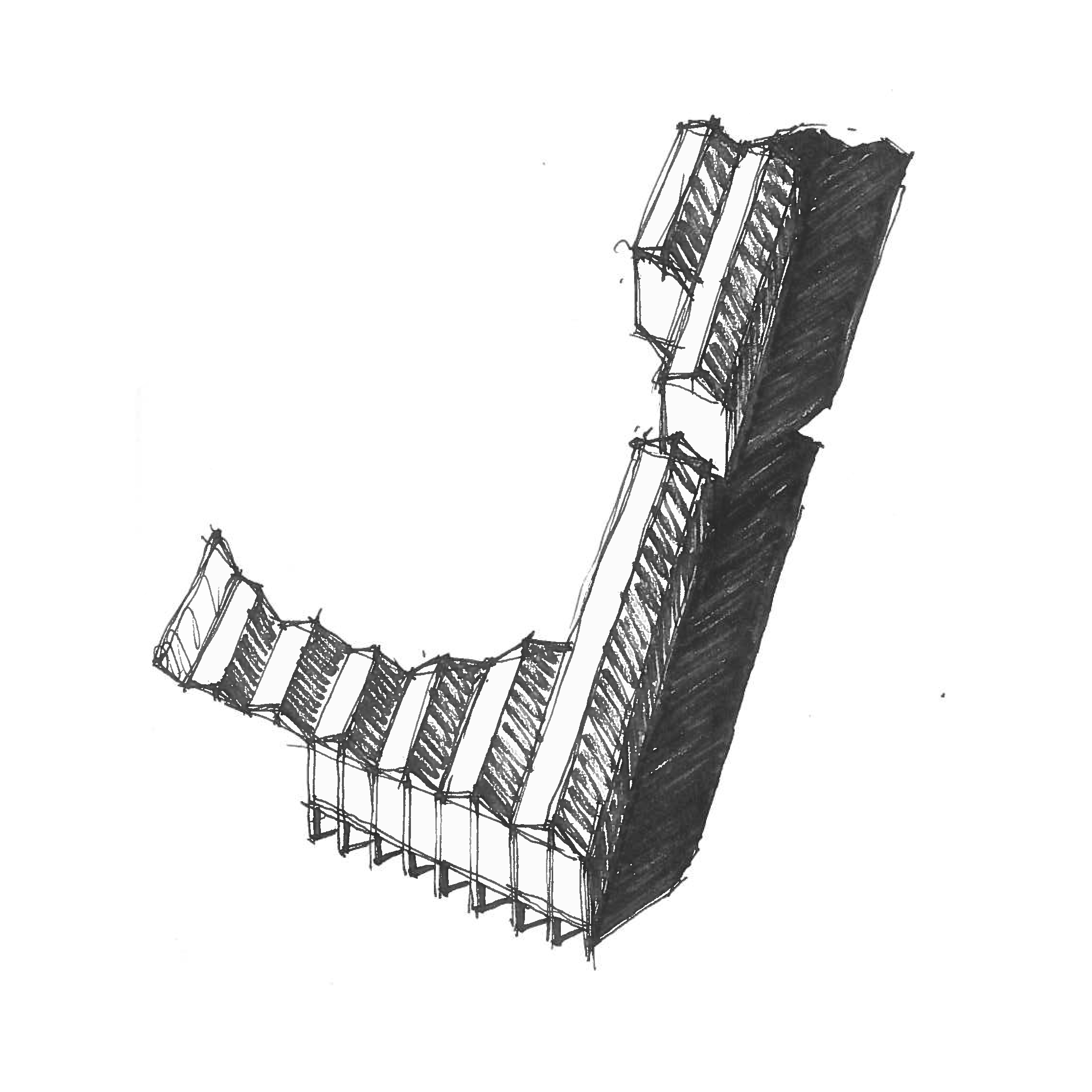

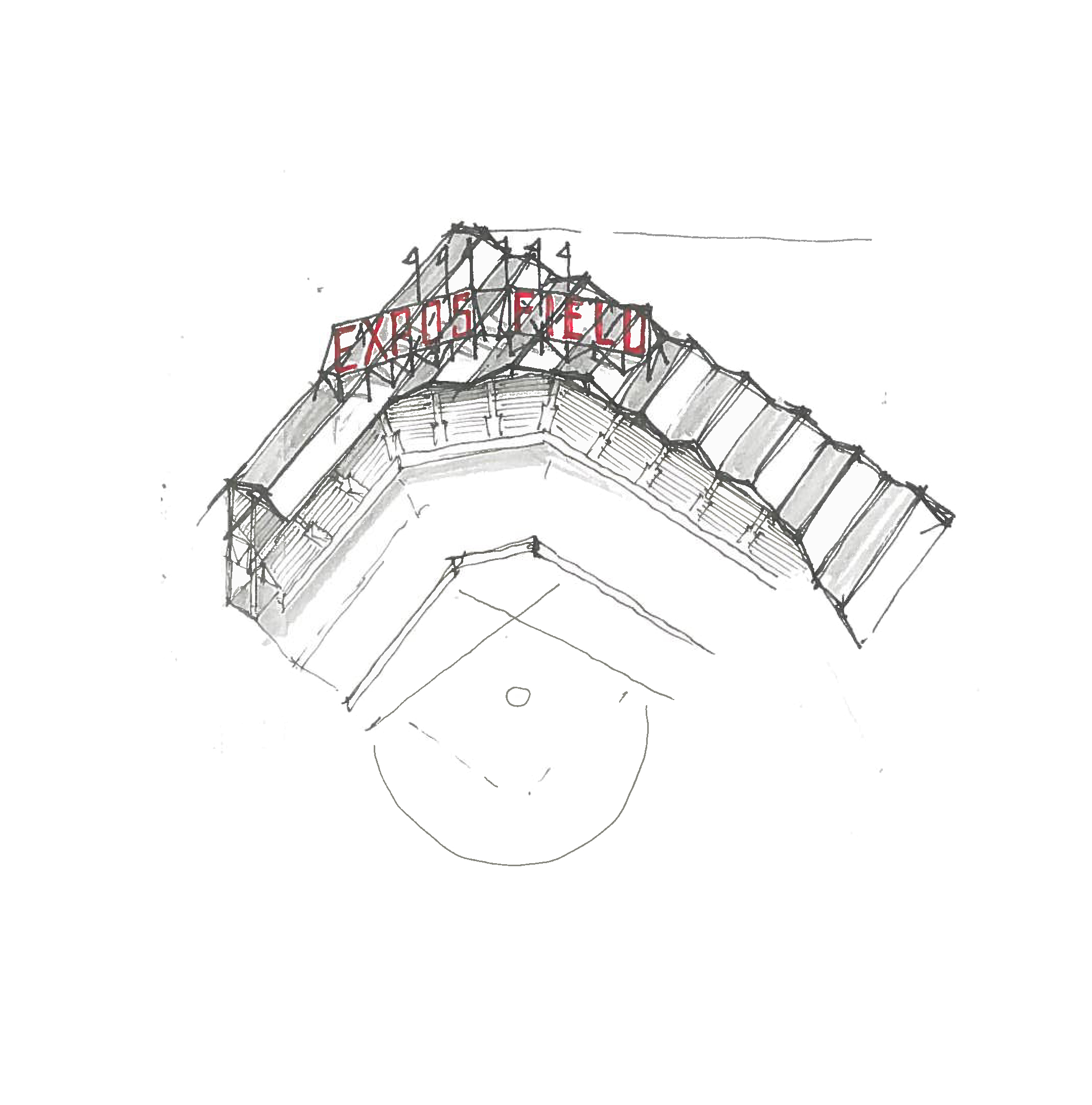

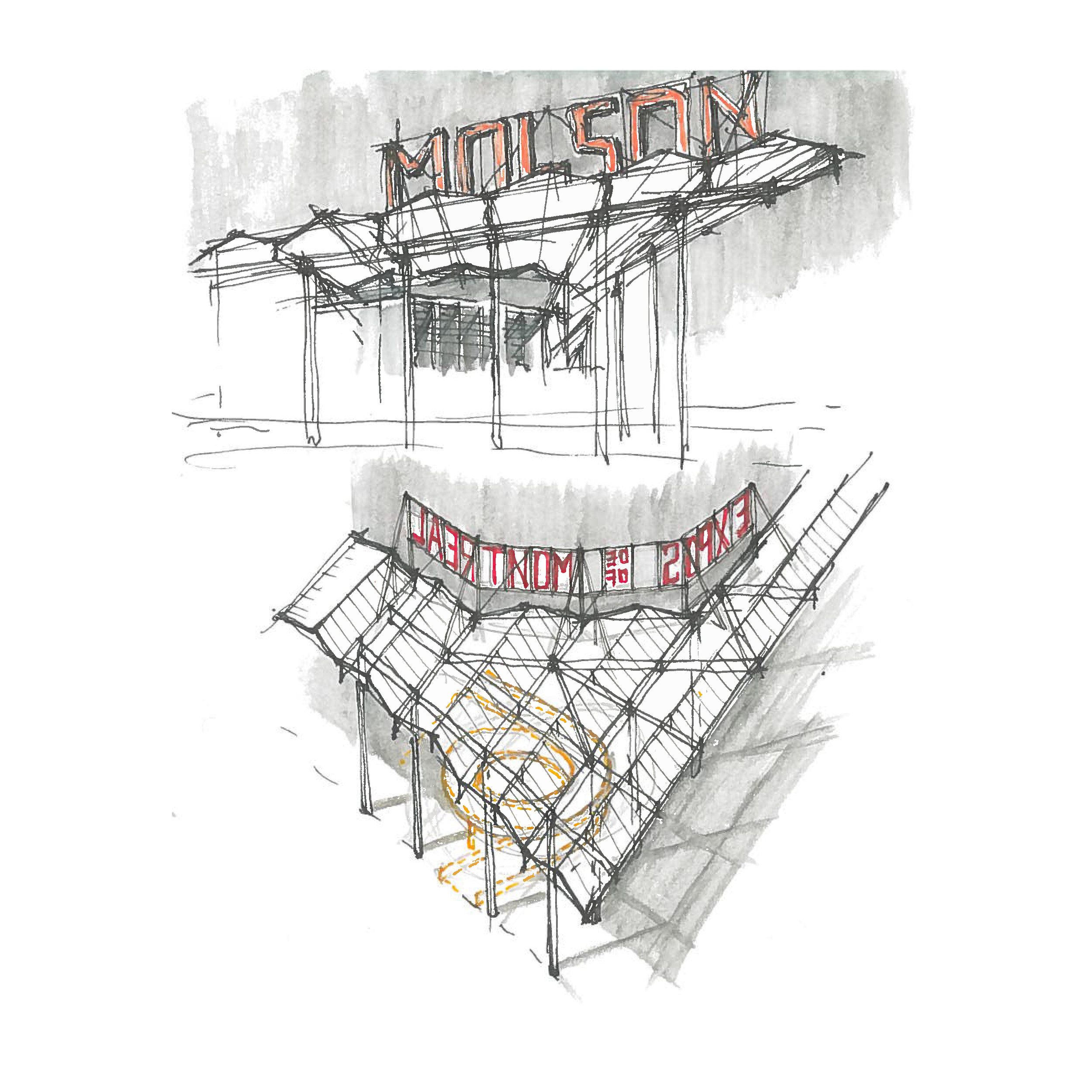

Following a year of research and a month of travel to the US, this thesis project breaks down to the traditional components of a ballpark—seating, public space, concessions—and weaves them into the vestigial elements of Montreal’s redeveloped Molson Brewery, a cherished historical landmark. The ballpark is no longer treated as a singular, hermetic building; now it's merged with new architectural programs and existing infrastructure (like a train yard), and within it is threaded a continuous public space at street level (coded in yellow in my drawings) that remains accessible all year round.

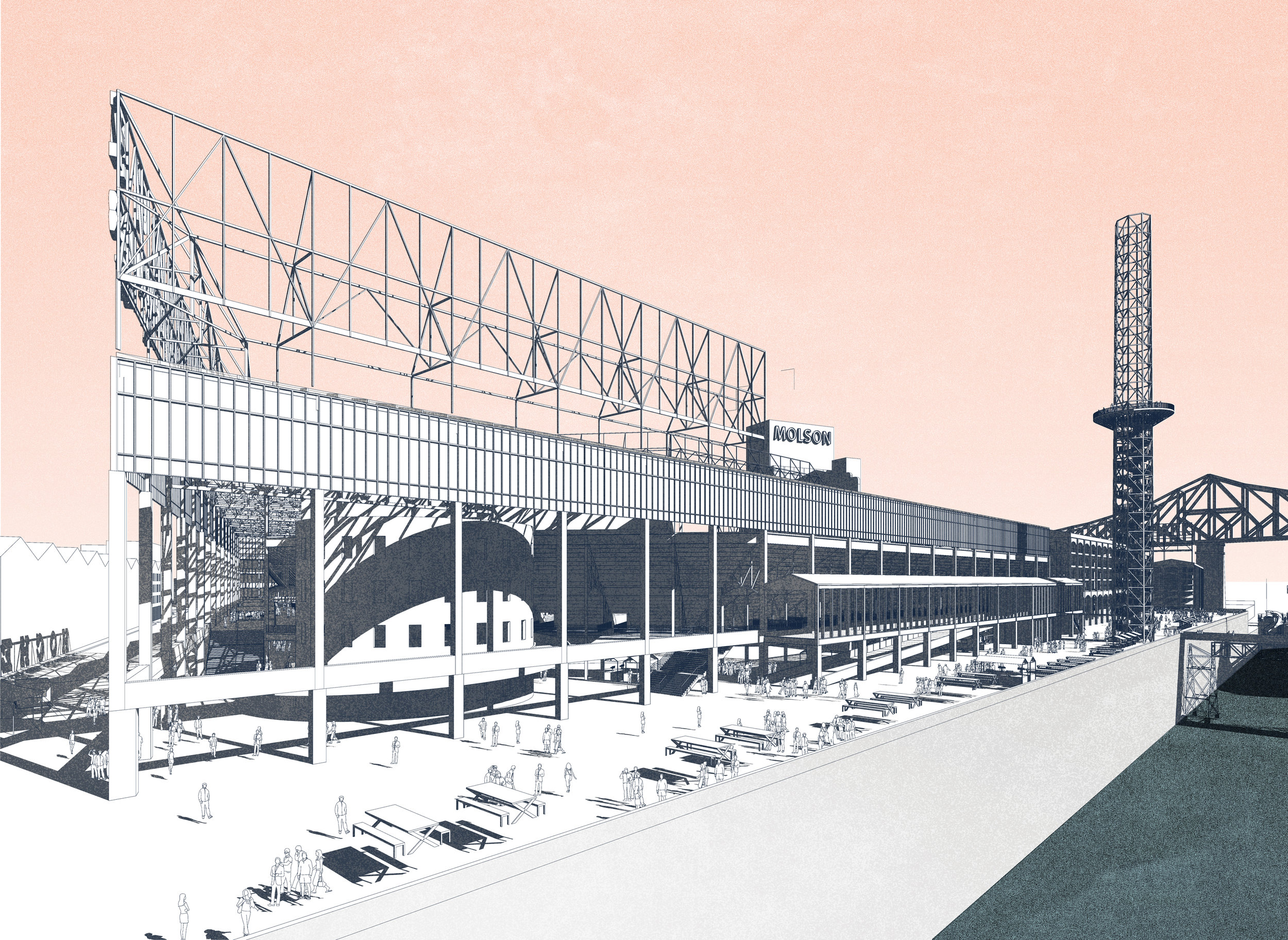

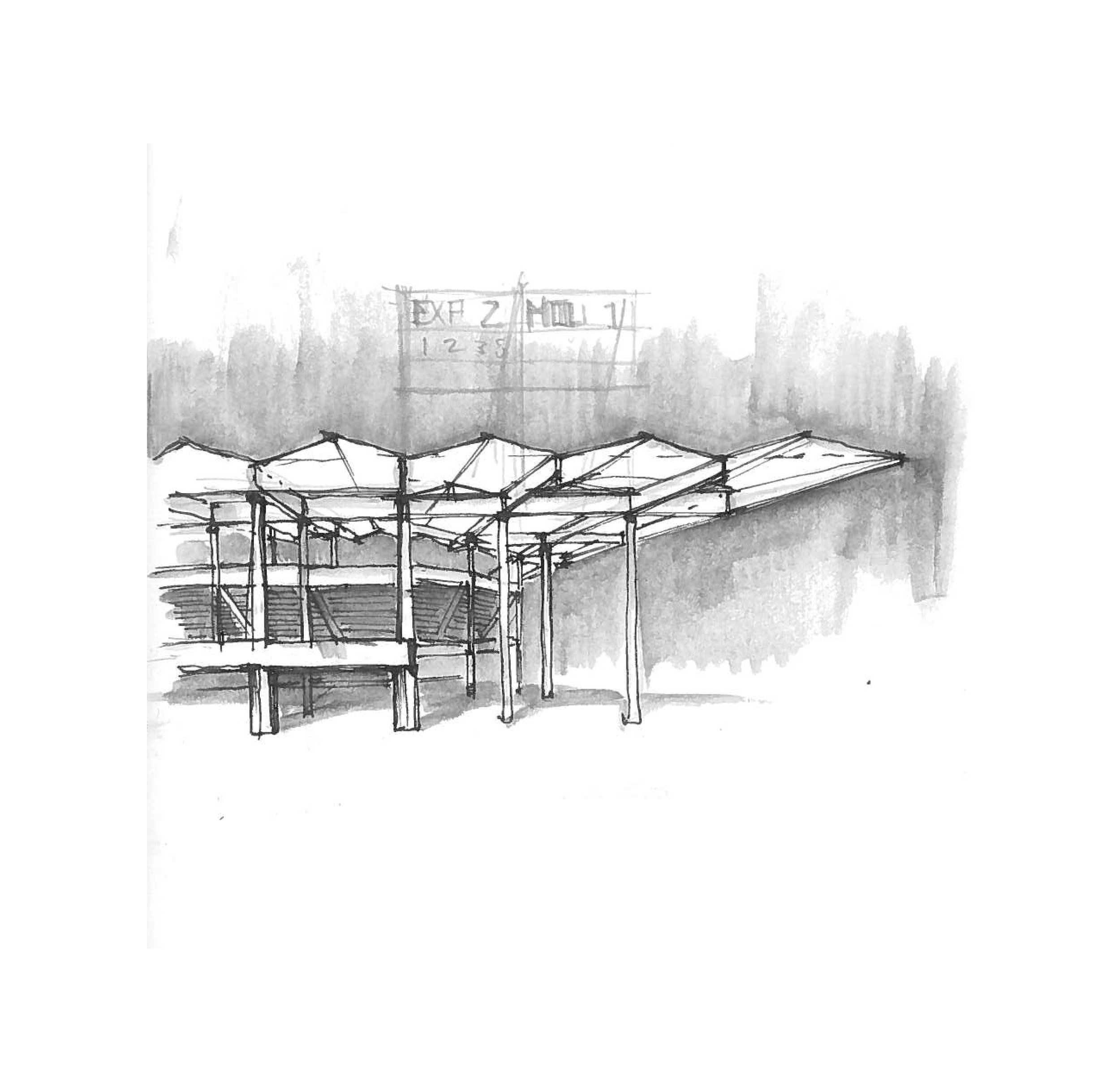

Food and drink concessions are arranged in a market hall along Notre Dame street, serving both the ballpark and the outside world. Along the same street, the brewery’s landmarked facades remain, hiding behind them a small multi-use pseudo-city. Neither the ballpark or the brewery (as it once did) block the waterfront from the street.

A simple industrial architectural language unifies these fragments, recalling the shipbuilding hangars and train sheds that were once ubiquitous along the surrounding Saint Lawrence waterfront. Perhaps like a train station, the ballpark is now a permeable node for people, commerce, and transit. But nothing is too polished; these are working buildings within a working city, and it remains a bit rough, perhaps a bit hectic, and completely contextual.

The project was presented at a final cirituqe at McGill's school of architecture with accompanying books that present my research and travels throughout the rust belt.